That’s what a Los Angeles driver asked me when he followed me into a mall parking lot after reading my license plate frame that reads:

I’D RATHER BE ON A BACKUP MALLET.

“I’m really into croquet but I’ve never heard of a backup mallet. Are you into Croquet?”

He was dead serious and was disappointed when he learned that it referred to a very special group of unique and powerful steam locomotives used only by the Southern Pacific Railroad. These locomotives are commonly known as a Cab Forward by people who are interested in railroads. Mallet, pronounced Mal’ ee, refers to a French dude, Monsieur Anatole Mallet, whose locomotive design concept was used in the early Cab Forwards built in 1909 but not in the later versions built between 1928 and 1944.

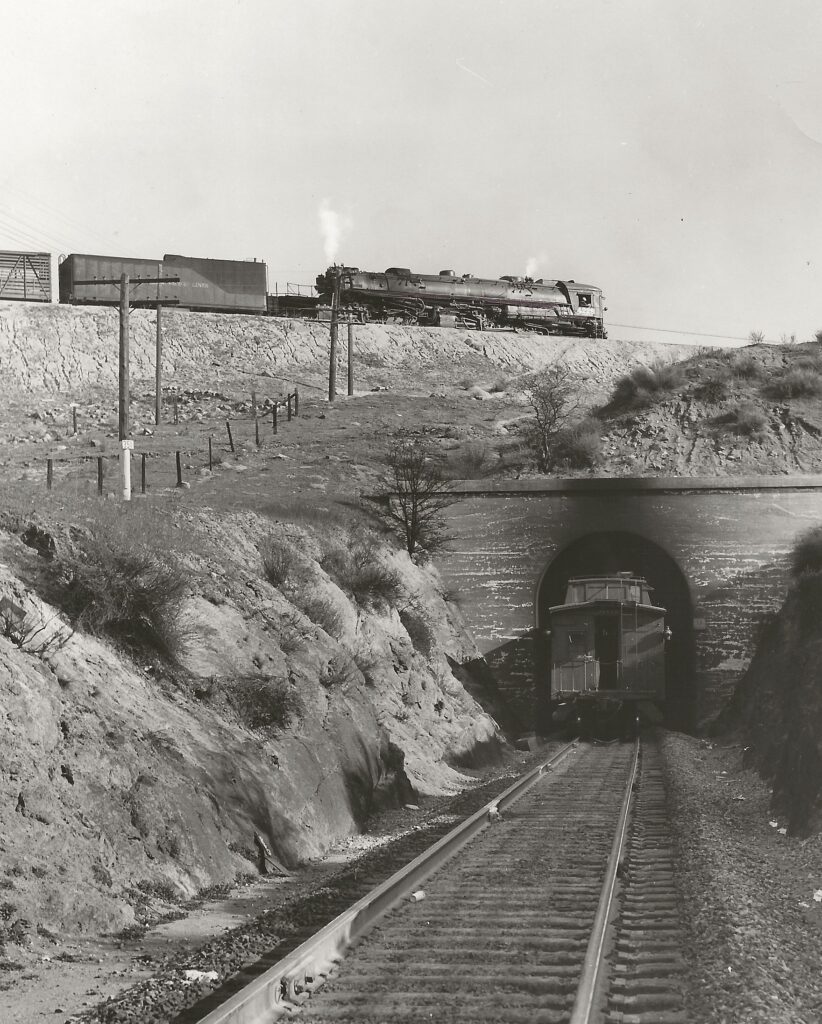

Mallet on a freight train coming off horseshoe curve at Caliente

Photo by: Stan Kistler

Cab forward engines were designed with the cab on the front and the smoke stack in the rear to put the engine crew ahead of the intense heat and smoke that blasted from the stack when they were confined inside the tunnels and snow sheds on the steep grade over Donner Pass. These engines were so successful that they were used on other heavy mountain grades, most especially over Tehachapi south of Bakersfield. Because they looked like a steam engine running backward and were a true Mallet compound engine, the early S.P. train and roundhouse crews called them a backup mallet or just plain mallet and that nickname stuck with all the cab forwards as far as the crews and shop people were concerned. Engine 4294, in the State Railroad Museum in Sacramento, is the final cab forward design and 144 were built between 1937 and 1944. The exhaust from the air pumps, above the monkey deck, gave these a distinctive “Pow–wheeze sound” that added animation to the normal exhaust blasts from the twin stacks that let everybody know a mallet was in town. These are the ones that I fired.

S.P. engine crew locker rooms had two posters that got attention from new firemen. One informed us that, due to the Korean conflict, railroads were the essential supply line and we could not strike; if we did, we would be drafted into the Army and then be assigned to operate the trains. Signed Harry S. Truman, President. We did not strike. The second poster pictured an S.P. engine with parts of its mangled boiler blown all over hell and a stern warning: DON’T LET LOW BOILER WATER DO THIS TO YOU! This was designed to put the fear of God into a new fireman—and it sure as shit did!

Since the mallet boilers are turned backward from an ordinary engine, there are many differences when it comes to working on them. Two differences were of special interest to me. The fireman’s controls and gauges are located beside the fireman instead of in front of us so it’s easier to fire a mallet with our back to the window; that places most of them in the same relative position as on a normal engine. It also makes it easy to look back toward the stack to see how well we are firing the engine. However, because of the engineer’s and fireman’s equipment racks being between us, we can’t see each other like we can on a conventional engine. Since it’s important for a fireman to know when the engineer changes the throttle or reverse gear settings so that he can readjust his firing controls, the engineer does a lot of yelling above the din of cab noise to the fireman when he makes changes. There are a few jerks who make sneaky changes without telling us and, on a mallet, these dudes are the shits to fire for because the water and steam is frequently out of sync with what the engine is actually using.

Mallet helper at Walong siding (pronounced Way-long) on Tehachapi Loop

Photo by: T.A. Johnson

By far the most important difference is that the levels in the mallet water glasses are the reverse of normal engines; they show more water than we actually have when we’re going downhill and less water than we actually have when we’re going uphill. Since Tehachapi is one of the steepest mainline grades on the S.P., this is extremely important to understand. Near the lower end of the fireman’s water glass is a metal plate with an arrow that warns, DO NOT LET WATER FALL BELOW THIS POINT. I put that in my memory bank.

I report to Bakersfield Crew Dispatcher’s Office for my first student trip on a mallet, a helper engine up the Tehachapi grade. Luckily, my engineer is Jimmy McCutcheon, a fine engineer whose sage comments were often recalled during my railroad career. Our train has eighty-five cars with a four unit diesel on the head end. Our mallet engine, the 4194, will be shoving on the rear ten cars ahead of the caboose. After leaving Bakersfield, except for a short stretch of steeper grade near Ilmon siding, for the first 18 miles, the grade is only about half as steep as it will be after we get to Caliente. Since we’re not working the engine hard right now, Dale, the fireman, satisfied with my efforts so far, is across the cab discussing baseball with Jimmy. Near Ilmon as the head end of our train starts up the short section of steeper grade, Jimmy stands up and yells, “Hey kiddo. Gonna work it a little more,” and he gives it more throttle. I increase the fire and the Worthington water pump but I’m startled when everything suddenly turns dark and noisy; we are in the first of fifteen tunnels. Outside again, my eyes readjust to the light. I see that the water in the glass is falling. I open the pump more hoping that it won’t cause me to lose steam which is right on 250 pounds. Our engine starts up the short section of steep grade, and the water drops just below the arrow on my water glass. My butt begins to pucker and a vision of the disemboweled engine poster flashes before my eyes. I increase the pump and adjust atomizer and fuel. Too much atomizer; the fire starts to drum. Damn! I cut the atomizer back a bit, but the water in the glass does begin to rise. Isolated behind my gauges and intent on watching the water level, I am unaware that the baseball bullshit has ceased and Jimmy is standing beside me. He’s smiling. I relax— kind of. “You’re doing a good job kiddo” he assures. “But dammit kid—-this isn’t a submarine.” He points back to the water from our stack raining down on the cars behind us; the caboose windows are all closed to keep the crew dry. An engine working water is something that we can’t ignore. Jimmy leaves Dale to do the teaching.

Dale talks loud over the cab noise. “First, ignore this piece of shit;” he points to the plate with the arrow. “On this hill, as you just found out on that little stretch of 2% grade, a mallet will work water unless we carry it near the bottom of the glass.” We slow the pump down a bit and wait for the water to drop. Approaching Caliente, Jimmy stands up and yells, “OK kiddo, it’s time to go to work!” and he shoves the throttle wide open. I put in a big fire then reach for the water pump valve. Dale shakes his head. As our train starts around Horseshoe curve at Caliente; I see the diesel on the headend of our train going up the hill in the opposite direction from the way our engine is headed. Tehachapi is full of similar sharp curves. The water in my glass is getting lower. I’m nervous as hell but Dale points across the cab to the engineer’s water glass. With the mallet leaning to the right on the super elevated curve, there is more than two inches of water in the engineer’s glass and it’s just “winking” in the bottom of my glass. Dale nods. Now, we increase the water pump. As the mallet levels out on a short straightaway, the water in both glasses is equal and mine is a bit below the arrow. All is copasetic. By comparing the water level in both glasses, I’m learning to calculate the actual water level as the grade, curves, and speed causes the water in the two glasses to fluctuate.

Mallet crossing over its own caboose, tunnel 9, the famous and much loved, Tehachapi Loop

Photographer unknown.

Passing through four short tunnels isn’t bad. Mainly it’s just dark with the deafening noise of our stack and the Pow–wheezing of our air pumps. The draft in tunnel 3 sucks the cap off my head. Crap! Tunnel 5, the longest, at 1175 feet; is hot from our firebox and gassy from our head end diesel exhaust but, thanks to the mallet design, the heat and gas from our own stack is behind us. We’re making 14 miles an hour so we don’t use the funnel-like breathing respirators; we just hold our breath as long as we can and soon we’re outside. If our train had three mallets or was only going 8 miles an hour, we’d probably use the respirators while going through tunnel 5.

After three more short tunnels we meet a Santa Fe freight and two mallet helpers returning to Bakersfield in the twin sidings at Rowen. By the time we stop at Woodford to take water, I’ve kept the steam pretty close to 250 pounds all the way and I haven’t had any more Old Faithful episodes erupting from the stack. We climb up to the monkey deck which covers the rear cylinders, past the “Pow—wheezing” air pumps and on up to the top of the tender. Dale warns, “Swing the spout into position before you open the cover. When you have the spout in the hatch, brace yourself on top of it before you open the water valve.” I give him the sure, I’ll remember nod. (If you don’t remember what happened on another mallet trip, go back to the previous post). While I take about 19,000 gallons of water, the rear brakeman walks by below and comments, “Guess I don’t need my raincoat anymore; you’re doin’ better.” I throw him a forced, screw you smile. We finish taking water and, with us shoving as hard as we can, the train finally starts to move out of Woodford. After rounding a few more sharp curves and crossing a couple of bridges, we see the diesel on our head end again. This time it’s 77 feet above tunnel 9 and it’s crossing over us on the Tehachapi Loop at Walong. We pass through more tunnels, meet an S.P. freight at Cable and, as the grade begins to level out, we pass Tehachapi depot. The hard push is over; only a mile and a half to the Summit. Dale smiles at me and nods. I relax. I think my first mallet trip went OK.

At the Summit, the brakeman cuts us loose from the train and we back the rear cars up so that we can head into the wye. I line the switches and we turn the engine while our diesel couples the train back together, makes a brake test and heads toward Mojave. We come out on the Main, run back to Tehachapi and tie the mallet down in track 2. We’ve been working for six hours; we’re hungry and we cross the street to the beanery.

With full bellies, we stroll toward our engine while Jimmy tells us a funny story. A three unit Santa Fe diesel is sitting on the Main beside our engine. The Santa Fe engineer tells Jimmy, “The Dispatcher wants you to couple on behind us and we will take you down with the dynamics so you won’t have to stop to cool the mallet wheels. He’s nervous; he wants us off the hill. He’s got some tonnage freights going east after 52 and 24 run.” We couple up behind the diesel and head off down the hill with the Santa Fe engineer having to do all the work.

Jimmy says, “You did OK, kiddo. You won’t have a damn bit of trouble with the mallets.” He and Dale resume talking baseball. I lean back and prop my feet up. All I have to do is keep a small fire to hold the steam at 250 pounds; with the Santa Fe crew doing all the work, we’ll only use enough steam to keep our air pumps working. It has been a good day. As I roll off Tehachapi hill enjoying a valley sunset, I feel good inside. “Pow—wheeze, Pow—wheeze”, all the way to Bakersfield.

This picture was taken of Tommy by Bonnie Adams at California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento, around 1990. She asked him to be a mallet engineer “model”. Look at that commanding position. The man clearly knows what he’s doing!

For more info about back-up mallets:

https://www.steamlocomotive.com/locobase.php?country=USA&wheel=4-8-8-2&railroad=sp#344