I was now a switchman, a professional railroader with my favorite railroad. I loved working there but it didn’t take long to find out that it’s a lot easier to railroad when you’re a high school kid doing fun things in the cab of the Elsie than it is having to deal with the reality of being a railroader. Fun crap like working with the grumpy guys who called the crews, having to learn the Book of Operating Rules—more importantly, understanding what all those damn rules meant—trying to understand the federal Hours of Service laws, but mostly, just trying to learn about working your new job.

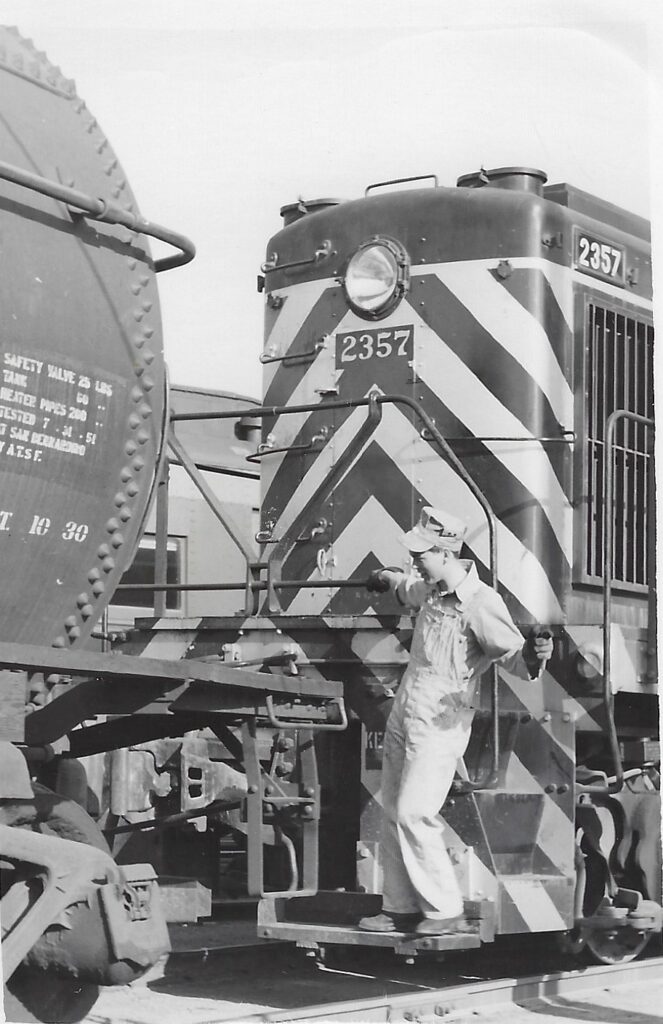

Tommy working on fireman’s side so that his Mom can take this picture.

Switchman, 1952.

Santa Fe’s Los Angeles yard had hundreds of tracks that stretched for ten miles. There were ninety switch engine assignments every day, each having its own specialized work to do. A new switchman learned the job by working with ten different crews in various parts of the yard. After those ten days, we were assigned to the Extra Board and we worked a different job with a different crew almost every day. During the first few weeks, we were frequently lost as we tried to lead our engine through the maze of tracks in the yard—much to the amusement or disgust of the old head switch crews and yardmasters.

Most of the men we worked with were lifetime railroaders; some just stayed for a while and faded away. A few were college guys working to pay their way through school. We made $12.75 for eight hours work which doesn’t seem like much now but that was good money in 1951. Some railroaders were pretty rough around the edges but most of the men were good guys to work with. If you paid attention and really tried to learn, most of them were helpful or at least tolerant of your efforts. I soon felt comfortable with the way I was able to do the work and, after I had a little seniority and could bid on jobs that I liked, I thoroughly enjoyed working as a Santa Fe switchman for eight months.

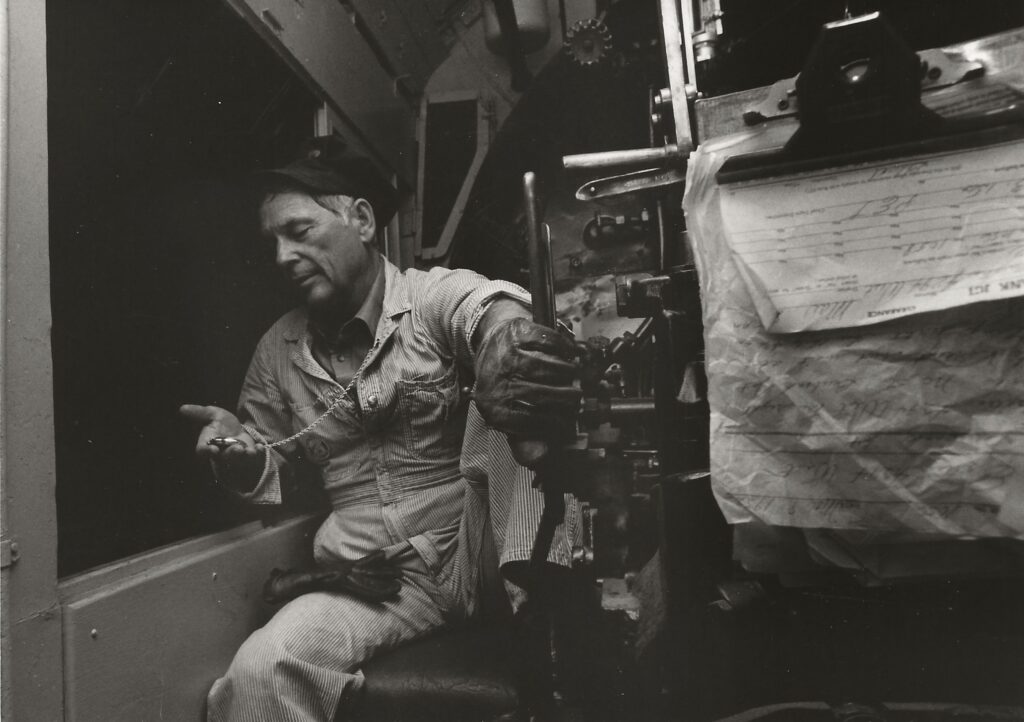

There was nothing like being a railroader, at least until the late 1980s. When I say “railroader” I’m not talking about the thousands of people who worked for the railroads. I’m talking about the train and engine crews, yardmasters, train dispatchers and officials who actually made the trains move. If a train was going to run, we were the folks who made it happen, 24 hours a day, rain or shine, in searing heat and freezing cold. It took a special breed of cat to do that day in and day out so let me talk a bit about those cats.

About 70 years before I arrived on the railroad scene, the expanding railroads were taking passengers and freight away from the stage coach and wagon companies. When those drivers, shotgun messengers and hostlers started losing their jobs, they packed their grips, put a 1/2 pint of whisky in their back pocket and hired out on the railroad where there were lots of jobs and good pay. Like driving horses, railroading was a rough, hard job and those men were rough, hard dudes and they were very independent of spirit. In other words, they didn’t take any bullshit off their fellow workers or their bosses. They had a hard job to do and they did it. Since they were no longer running horses down a lonesome, dusty trail in the wilderness but were now confined to interacting with other trains on a single track, the railroad companies soon put a big hammer on their 1/2 pint in the hip pocket shit but they did not try to do much about their independent spirit, not if they expected to move those steam powered trains across prairies and over mountain passes like Donner and Raton.

By 1952, the railroad was more civilized but I did fire steam engines for men who had hired out between 1905 and 1915. Although they had pretty much substituted a jug of coffee for the1/2 pint, many of them were relatively unchanged from the day they hired out on the railroad. I had the good fortune to work with these men as well as many fine and much younger engineers who showed me what railroading was all about. As strange as it sounds, this happened on the Southern Pacific Railroad and not on my favorite line, the Santa Fe.

Why did I switch to the S.P? Love! I switched for Love, or at least what a boy thinks is love when he’s 18 years old. Her name was Carol and she lived in Porterville, 160 miles away, a five hour drive from Los Angeles, damn sure too many miles for a guy in love. In April, 1952, S.P. was hiring new firemen and most of them would work in Bakersfield and Fresno. Porterville is 50 miles, more or less, from those two cities, something that my ’41 Chevy could cover in either direction in less than an hour. Sure, I wouldn’t be working for Santa Fe but there are priorities in life and Carol was definitely the higher priority.

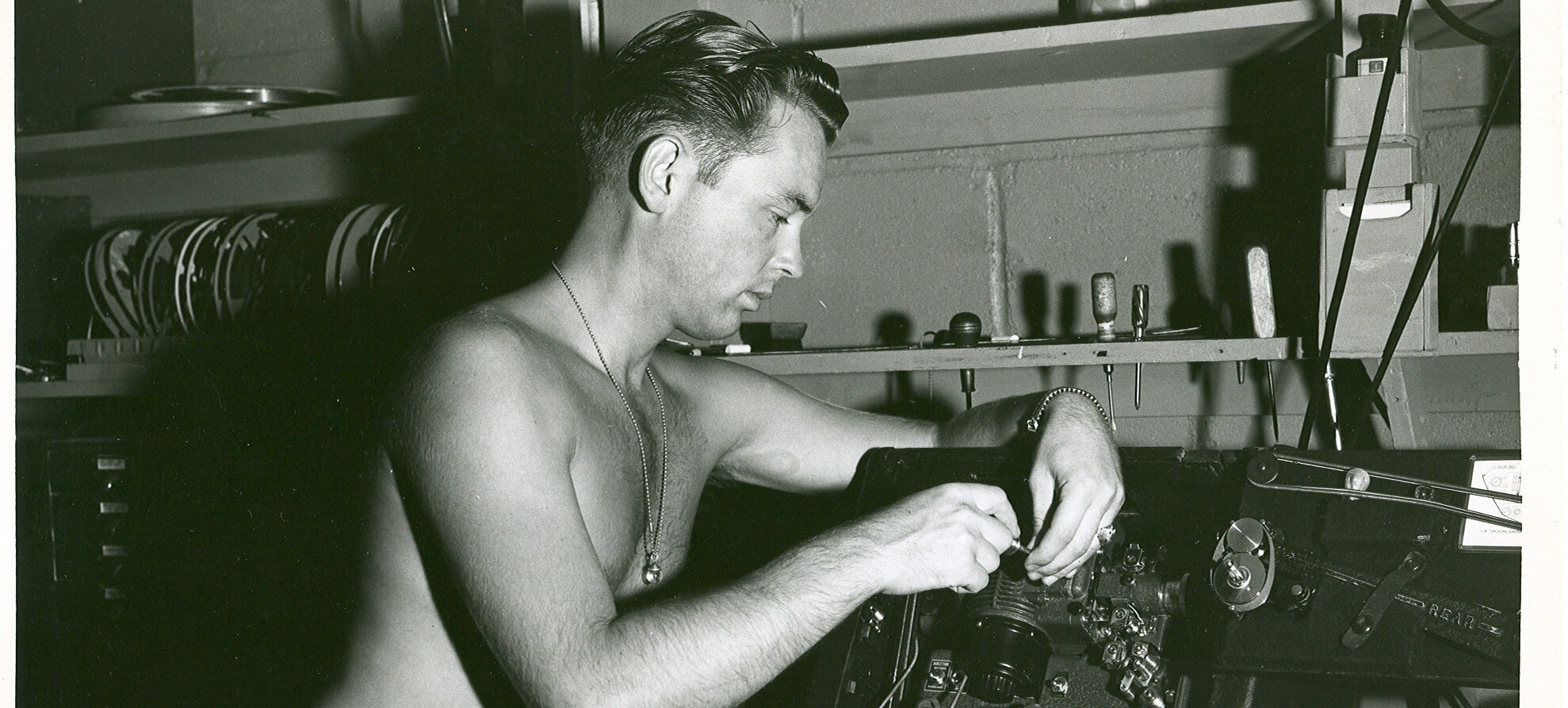

After taking a brief physical, a Book of Rules test and proving that I had a reliable railroad pocket watch, I was given seventeen letters of introduction to engineers authorizing me to make student trips on a yard engine and on sixteen mainline freight trains. Student firemen made a round trip Bakersfield to Fresno, six helper trips up Tehachapi grade, two round trips Los Angeles to Bakersfield and two round trips Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, a total of 480 miles of main line, over which a fireman was then expected to be able to fire a steam engine and to have some idea of how to keep the motors running if we got called for a diesel run out of Los Angeles. However, these letters of introduction did not require a student to go with a specific engineer nor did they require an engineer to take a student. It was up to us to talk one of the engineers making that run into taking us with him.

The yard engine was easy but the Bakersfield to Fresno engineer that I asked, G. Ballard, snapped, “I don’t take students.” Coming to my rescue, his fireman said, “Aw, screw the old bastard. I’m Jesse. Come with me kid.” After going through the predeparture duties and getting the boiler pressure up to 200 psi, we were slowly pulling out of the yard to the main line and Ballard had the throttle open just enough to move the train. Over the noise in the cab, Jesse explained the basics of firing.

“OK, Tommy, when the front of this engine gets to Chester Avenue and we see that the traffic is stopped, Ballard’s going to lay that throttle right out against the tank (railroad talk for pulling the throttle wide open). Don’t be timid. Stay with him. The instant that steam gauge drops one pound, put more fire in the box. Do it right now! Don’t hesitate! Keep as big a fire as you can. Don’t smoke it too much; you’ll waste fuel and screw up the flues; then you’ll have to sand the hell out of them to clean ‘em out or the engine won’t steam worth a crap. Keep ahead of Ballard because you’ll probably lose another five pounds before you get it back on the peg. Then start your water pump. But not too much. Watch your steam gauge. Watch your water glass. Don’t be putting more water in the boiler than you’re using. If you keep losing steam, you’ll be in deep shit for miles and Ballard can’t help you because he’s got 5300 tons of train to move as fast as this engine can roll. That’s what they’re paying him to do, right? It’s your job to give him a full head of steam, the power to do what he has to do. You get what I’m saying, kid? Even if you don’t like the ol’ son of a bitch, it’s a joint effort between the engineer and the fireman. Remember Tommy, always a joint effort. Your job is to make steam for him. That’s what you do. OK?”

The whistle drowned out his words as Ballard gave a warning to the cars and, with the throttle out against the tank, we blasted across Chester Avenue. We were on our way. I held my breath. With coaching from Jesse, I held on to the steam and water. I finally started to breathe again. I smiled at Jesse. He smiled back. All in all, I did pretty well for most of the way and by the time we got to Fresno six hours later, I felt good about my first student trip on the road. As we left the engine tie-up track at New Yard, Ballard, other than writing did OK and signing his name to my letter, never acknowledged that I was in his cab.

Downtown at the Greek’s cafe on Fulton Street, Jesse introduced me to engineer, F. O. Wilson, known as Foo Wilson. After he ate his $1.25 steak dinner, he was to leave for Bakersfield. He agreed to take me and asked me to join him for dinner. Our train returned on the alternate route through Exeter, longer and slower, winding through the orange groves. Although it was a good, easy trip, it took 14 hours to get to Bakersfield and I’d been up for almost 24 hours so I got a room at the Imperial, a hotel used by S.P. crews, and slept a while before I made the drive to Porterville, a straight shot road that I would drive many times. Later, between student trips on the Tehachapi helper engines, I plotted out the best route between Porterville and Fresno’s New Yard because I knew that, sooner or later, I’d have to work in Fresno and I wanted to be sure of the quickest way to get back to work after spending the day with Carol.

At Bakersfield, Fresno and Santa Barbara, there were hotels and cafes that catered to S.P. crews who were laying over away from their home terminal. The simple rooms cost a dollar because we usually only spent 6 to 9 hours in these rooms. Each guy that we worked with had his preferred hotel and eating places and, as a student, we usually tagged along with our fireman and went to cafes where he ate and hotels where he slept.

After making my first student trip to Santa Barbara, the crew wagon dropped us off at State Street near the passenger depot. I accompanied my fireman a short half block to a small building with a bar downstairs and a hotel upstairs. With the sounds of a jazz combo emanating from the bar, we paid the man for our rooms, went upstairs and down a dimly lit hall, passing a girl and guy leaning against the wall looking like they would soon be using one of the rooms. I found my room and crashed. Next morning, the callboy knocked on my door and gave me a one hour call for my train back to LA. Since it only took us five hours to get to LA, I grabbed a burger, then made my other student trip to Santa Barbara with a different crew.

At Santa Barbara, the wagon dropped us off at State Street and I started immediately for the hotel to show them that I knew how things were done.

One of the crew yelled, “Hey, Johnson, where are you going?”

I proudly said, “To the hotel.”

There was a burst of laughter. “Well, we know which fireman you came with on your first trip. He’s the only one who stays at the whore house. The rest of us stay over here at the Southern.” Sheepishly, I followed them across State Street to the hotel.

I entered the lobby of the Southern and was suddenly transported to 1930. A rather simple front desk was surrounded by several heavy rocking chairs and a couple of leather covered sofas; all were of Craftsman design, early 20th Century. They faced the large plate glass window that looked out toward State Street and the S.P. tracks. Three gentlemen in bib overalls sat in them, waiting for the call for their next run to Los Angeles or San Luis Obispo. I went to my room feeling that I was part of something very historic, in a place that had looked like this for many years. But, that spell was broken in the early morning hours when the callboy woke me up for the return trip to LA; the engine would be one of the brand new diesels.

About ninety percent of the engines on the San Joaquin Division at that time were still steam engines. A steam engine on the mountain run from Bakersfield to LA would use over 50,000 gallons of water; in the valley, over 25,000 gallons to get from Bakersfield to Fresno. Student firemen learned a lot about water. First and foremost we learned how to maintain enough water in the boiler to keep the engine from blowing up. As a reminder, S.P. had a large poster in every enginemen’s locker room that showed the mangled remains of a 5000 Class engine that blew up in Arizona. In large bold letters the poster warned:

DON’T LET LOW WATER DO THIS TO YOU!

I know this isn’t an SP engine, it’s actually a B&O engine from back east. But isn’t this a great photo?

A fireman taking water with water gushing over the top.

On freight and passenger trains, the fireman had to take water from the water columns along the mainline and that could become a bit precarious if you were careless. Some columns had been there a long time and were difficult to swing over the tender. The force of the water coming out of a ten inch water column is tremendous and it could change the angle of the spout and knock you off the tender if you weren’t properly braced. Suggestions from the firemen while we were students in training got pretty repetitious and we always nodded and said we’d remember what they had told us.

Two warnings that were most often repeated were:

No. 1: Do not open the cover on the hatch before you wrestle with the big hook trying to swing the spout around over the tender. Always, swing the spout out over the hatch with the cover closed, then open the cover. To answer your questions:

YES, you can fall in.

YES, most firemen will fit though that 28 inch hatch.

YES, more than one fireman has ended up getting a complementary S.P. bath when

he forgot about the open cover as he strained to swing the spout around.

YES STUPID, there is a ladder inside the tank to help you crawl out.

No. 2: Before opening the valve on the water column, make sure that the spout is completely and properly placed in the open hatch and that you are standing on the spout and that you are securely braced to hold it in the hatch when the surge of water comes.

Open the valve slowly, then increase the flow. Very simple instructions but easily ignored by an eighteen year old in love.

Question No. 1: Did I do that when I was a fireman? YES.

Question No. 2: Always? Well—all but once!

Once upon a time, while taking water on the side of Tehachapi mountain, I was having trouble getting the spout to swing around over the tender. When it finally did move with a lurch, the hook slipped off the spout but I hugged the spout and didn’t fall off the tender. (So far, so good). Frustrated, I opened the hatch cover and slammed the spout down, not noticing that it wasn’t entirely inside the opening. (Not good to ignore). I had one foot on the spout but I wasn’t really bracing myself properly. (Another, not good). For good measure, I added another not good idea (I opened the valve too fast). The sudden rush of high pressure water momentarily jerked the spout up out of the hatch, flooding the top of the tender and drenched me from head to toe. Besides feeling like an idiot I was pissed. After I gave up and did it right, for twenty minutes I felt and looked like a drowned rat while I stood on that tender and finished taking water. Down on the ground, the brakeman had a shit-eatin’ grin on his face every time he looked up at me. Back in the cab, I stood there sopping wet. I was not amused when I looked at my engineer; it was the only time I ever saw Steele laugh. My eyes telegraphed a “screw you old man” message across the cab. He quit laughing and turned to look out the window but I could tell by the way his body was quivering he was laughing again.

Since we were soon going to stop for “beans” in Mojave, I had to dry out quick. I pulled off my clothes and draped them over pipes, valves and gauges; the cab looked like a Chinese laundry after an explosion. From Woodford, I fired the engine dressed only in my boots. Steele shook his head in disbelief. He didn’t laugh any more but I knew he was quietly chuckling inside and I was expecting him to erupt any minute. The heat from the boiler soon dried my clothes and I did manage to get dressed in time to go to dinner at Reno’s Cafe with the rest of the crew. Within two days everybody on the San Joaquin Division knew about The Naked Railroader on Tehachapi mountain.

Love this! Thank you for answering the question of how the title came about ?